It’s interesting how the word “vanish” works. In a magic trick, when something vanishes, it seems to disappear without a trace. But does that mean it’s truly gone? What if it still exists in our minds or hearts? Sometimes, collective memory can be just as powerful — if not more so — than physical reality.

Cynthia Brothers brought these ideas to life eight years ago when she started a social-media project to document and honor familiar local spots that seem to fade from sight every day. She called it Vanishing Seattle.

Now 43, Brothers has grown her movement, which is mostly run by volunteers and supported by some grants, to 117,000 followers. Last year, she hosted a vibrant exhibit in Pioneer Square, and this year, she published a book, Signs of Vanishing Seattle, which revives memories of more than 75 lost landmarks through their iconic signage.

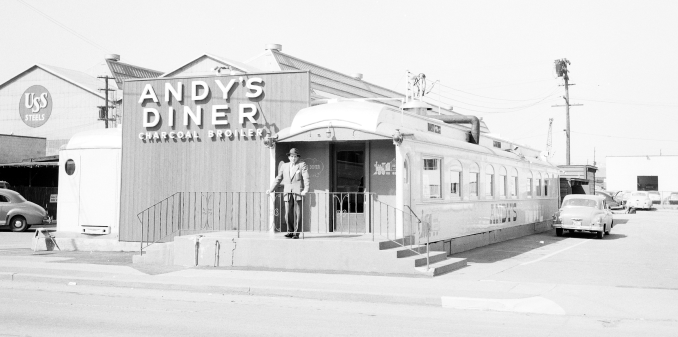

One of these is Andy’s Diner. If you’ve moved to Seattle since 2008, you might not recognize this simple diner on Fourth Avenue South by its original name. For the past 16 years, it has been the Orient Express, a Chinese restaurant and karaoke bar.

Before stadiums transformed the Sodo neighborhood, Andy’s Diner was part of the area’s industrial charm, crafting a unique identity with a building made from old railroad cars, visible from the busy street.

In 1949, Andy Nagy opened his first car diner at 2711 Fourth Ave. S. He was later joined by his nephew, Andy Yurkanin, in 1955. The two moved the diner two blocks south in 1956 and expanded it to include seven cars. They transformed it into a popular steakhouse and banquet facility, becoming a local food-service staple beloved by many, including hungry newswriters.

Railcar diners weren’t unique, especially with their strong roots in the East, but Andy’s Diner stood out due to its fun and memorable image. “We are after a tradition, an atmosphere,” Nagy explained to Seattle Post-Intelligencer columnist Emmett Watson in 1959. A 1973 headline in The Seattle Times even added a playful pun: “Choo Choo Chew Chew.”

This quirky charm is why Cynthia Brothers holds such affection for the iconic Andy’s Diner sign, which collector John Bennett loaned for last year’s exhibit and included in her book, Signs of Vanishing Seattle. The book features a range of other Seattle landmarks, from music venues and LGBTQ+ bars to record stores, shoe shops, and antique stores.

Some signs still remain, though many, like Andy’s, have been altered or completely disappeared. The book compares these signs to rabbits pulled from a magician’s hat.

For Brothers, these signs represent “love letters to the sign artisans and social landmarks that gave our city its soul, and a testament to their lasting impact and legacies that are still felt today.”

Leave a Reply